It was a day in late August 2019 when the poet and artwork critic Peter Schjeldahl first obtained the decision from his physician with the information that his lung most cancers had unfold. He was driving to satisfy his spouse, Brooke, at their nation home at Bovina, within the Catskills. Patsy Cline’s Walkin’ After Midnight performed on the automotive radio and Schjeldahl had simply hit mile 81 of the New York State Thruway. The rising mountains reminded him of a revelatory Thomas Cole portray; the hills unfold out earlier than him, and he mirrored on the historical past of how lengthy painters had painted these mountains. Schjeldahl recounts the second in “The Artwork of Dying” (The New Yorker, 2019), a long-form essay and significant street journey by way of his life in artwork, wherein he characteristically discovers the rising potentialities of portray in essentially the most unlikely locations. He was an indispensable artwork critic who wrote with the lyric observations of a poet.

Schjeldahl’s direct and unflinching prose made an enemy of complacent or proudly dissatisfied artwork writing that had little private use for artwork. A revered poet in addition to a critic, he was a lifelong fanatic for portray, for New York, and for the reparative potentialities of artwork throughout occasions of non-public and collective disaster. “I’ve by no means stored a diary or a journal, as a result of I get spooked by addressing nobody,” he wrote, “After I write, it’s to attach.” Regardless of the anguish of residing with a terminal sickness, his physique enjoying host, in his personal phrases, “to a gang conflict between the immunotherapy and the most cancers, with each residing off the land”, he continued to jot down fluent and eloquent criticism all through his ultimate summer season.

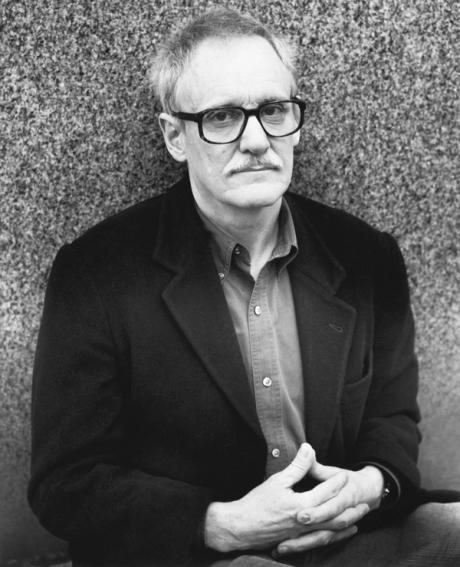

On the time of his demise, Schjeldahl was 80 and the long-time artwork critic at The New Yorker, which he initially joined as a employees author in 1998. Commanding an unmistakable important voice, which frequently blended wry humour with forensic observations on the play of pigment and line, Schjeldahl’s artwork writing appeared in Artforum, Artwork in America, the New York Occasions Journal and Vogue. It was produced over 50 or so years in the identical research of his top-floor East Village walk-up house. However regardless of the shiny glamour of those severe and middlebrow magazines, he at all times wrote about New York with the verve of an outsider, a grasp navigator of what right this moment we’d name the excessive/low in cultural manufacturing.

Schjeldahl grew up within the snow-flecked gray of the Midwest. Born in Fargo, North Dakota, he was the oldest of 5 raised by a “prairie princess” mom, Charlene, and a working-class hero father, Gilmore, in provincial Minnesota. The patented innovations that made Schjeldahl’s father reasonably profitable—a broadly rolled-out airsickness plastic bag, after which the NASA Echo 1 and Echo 2 Mylar-balloon satellites—led to his son being considered “the wealthy child” when he smoked cigarettes as a 16-year-old behind the high-school soccer bleachers in Northfield, Minnesota.

The household gathered each week to look at The Ed Sullivan Present, together with one time in 1956 when Elvis Presley got here on and adjusted every part. It’s simple to see how early experiences like these marked a lot of the prose that got here after. First, Schjeldahl felt the double-bind of each smalltown child who manages to get out: the light contempt for anybody who doesn’t wish to stay their life on the teeming centre of issues, combined with discovering himself in artwork by understanding what life is like for these underprivileged who don’t communicate Worldwide Artwork English exterior the cliquish citadels of blue-chip galleries. It’s a uncommon double qualification right this moment. In “Andy Warhol”, as an illustration, the primary collected essay within the infuriatingly readable Scorching, Chilly, Heavy, Mild: 100 Artwork Writings 1988-2018 (2019), he celebrates Warhol not as a perverse ironist, however as a working-class boy who had the creativeness to take “the format of Barnett Newman and put Elvis Presley on the entrance”.

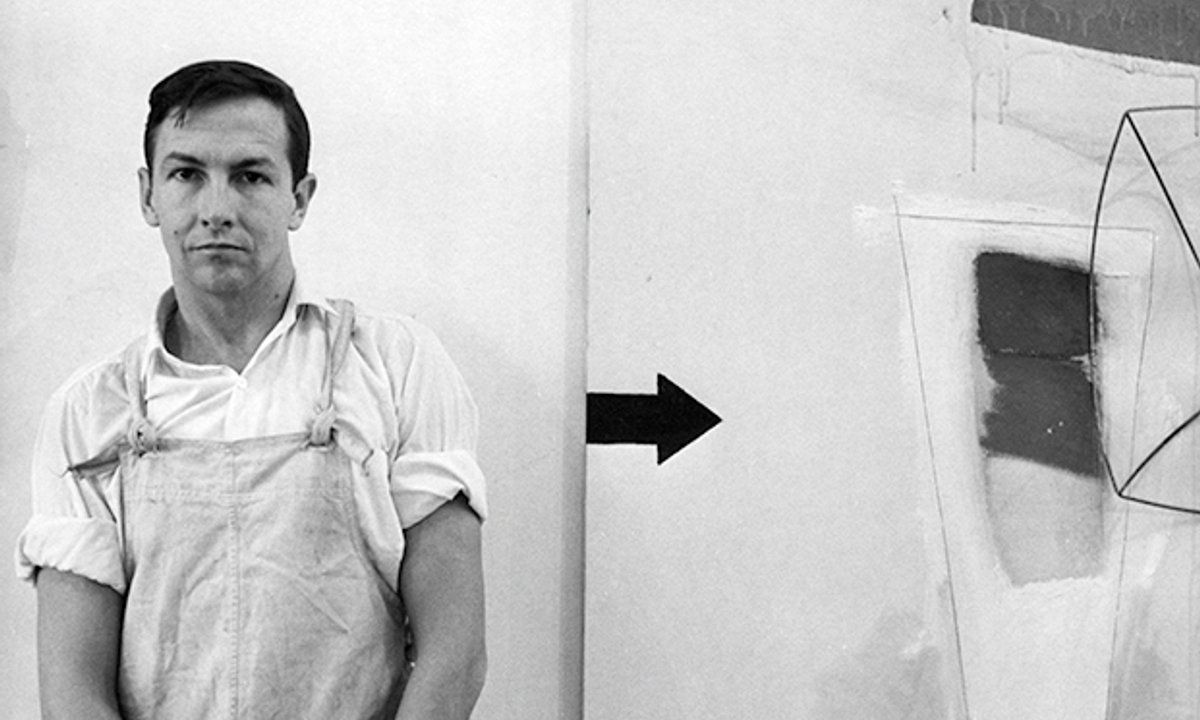

Mixing confidence and self-deprecation, Schjedldahl stated that the “solely factor that I’m a world professional in is my very own expertise”

Regardless of enrolling twice on the personal liberal arts Carleton School, in Northfield, between 1962 and 1964, after which for a quick and unproductive spell at The New Faculty in Manhattan, Schjeldahl acknowledged {that a} “highschool diploma was [his] biggest achievement”. This was not strictly true, as he went on to obtain a number of prestigious and honorary awards, together with the Frank Jewett Mather Award from the School Artwork Affiliation, for excellence in artwork criticism; the Howard Vursell Memorial Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, for “latest prose that deserves recognition for the standard of its type”; and, not least, a Guggenheim Fellowship grant, from which he used a lot of the cash to purchase a backyard tractor at Bovina. However Schjeldahl’s poor grades and anti-

tutorial credentials solely got here to be a energy of favor. Mixing confidence and self-deprecation, he stated that the “solely factor that I’m a world professional in is my very own expertise”. He was that uncommon author whose description of encountering artwork made the reader really feel that they have been experiencing it, too. He privileged an embodied expertise of artwork, of writing that obstinately emerges from being there with the work itself, and that celebrates portray’s skill to mix “our strongest sense”, sight, and “our biggest bodily aptitude, the hand”: “that’s why I exploit the primary individual”.

After a brief spell in Paris, which he didn’t suppose was all that great, Schjeldahl settled in Greenwich Village and immersed himself within the downtown poetry scene. “For a couple of dozen years” within the lengthy Sixties, Schjeldahl mirrored in 2019, “I frolicked, drank, and slept with artists who didn’t take me severely. I noticed, heard, overheard, and absorbed an incredible deal.” He barely slept in order that he may make the utmost variety of errors. One temporary but fortuitous encounter in these heady days was with Frank O’Hara, the poet and Museum of Trendy Artwork curator whose occasional poems typically really feel proximate to pushing your ear to the brownstone wall and eavesdropping in your extra thrilling neighbour’s gossip from the night time earlier than. He referred to as them “private poems”. O’Hara stood as a type of protector for an urbane and gregarious writerly sensibility that the youthful poet-critic was starting to domesticate.

Round a yr later, in July 1966, O’Hara died in a dune buggy accident on Hearth Island. Schjeldahl penned a celebrated obituary in The Village Voice (the place he was later artwork critic from 1990 to 1998): “Every little thing about O’Hara is straightforward to reveal and exceedingly tough to ‘perceive’,” he wrote with attribute readability. “And the aura of the legendary, by no means removed from him whereas he lived, now appears about to engulf the reminiscence of all he was and did.” The identical may be stated of Schjeldahl.

Within the Nineteen Seventies, Schjeldahl got down to work on an in the end deserted biography of O’Hara, and recorded tons of of hours of interviews with the survivors and hangers-on of the New York scene. The mission was resuscitated from the reducing room flooring when Ada Calhoun, Peter and Brooke’s solely baby and a diligent author, found the recordings accidentally. In June 2022 she revealed the broadly acclaimed Additionally a Poet: Frank O’Hara, My Father, and Me, a young and hilarious portrait of a author and father, who could have had shortcomings within the latter position however who by no means missed as a chronicler of New York’s artwork scene in the course of the course of half a century. “I at all times stated that when my time got here, I’d wish to go quick,” he mirrored in “The Artwork of Dying”. “However the place’s the enjoyable in that?”

• Peter Schjeldahl, born Fargo, North Dakota, 20 March 1942; married Donnie Brooke Alderson (one daughter); died Bovina, New York, 21 October 2022.